In 35 years of reporting on China and its emergence as a global power, perhaps the most perceptive and certainly the most genial person I met was Cao Siyuan. He was by no means grand. His face looked as if it had been moulded by laughter. He laughed frequently, often at his own jokes and sometimes at himself. He had once, before a dramatic fall from grace, been an adviser to China’s top leader. But when asked about his time among the ruling elite, he would demur, describing himself as no more than a “seventh-grade, sesame seed-sized official”.

Cao died in 2014 at the age of 68. But his turbulent career trying to coax reform out of China’s single-party state reflected a much bigger historical struggle that has characterised the rule of the Chinese Communist party, which marks its 100th anniversary on July 1. His experiences also put into human context the knot of tensions that still reside at the heart of CCP rule and govern many aspects of China’s increasingly fractious relationship with the outside world.

Cao was known in China simply as “Mr Bankruptcy”. The name came because he was the architect in the 1980s of the country’s first bankruptcy law. This may not sound like much but at that time bankruptcy was at the ideological frontier of China’s transition from Maoist communism to the hybrid system of market authoritarianism that it adheres to today.

Communism, after all, was all about output; it did not recognise profit and loss. But bankruptcy not only recognised financial performance, it made it the basis for corporate survival. Thus the bankruptcy law that Cao pioneered helped to consign the old “iron rice bowl” economy to history and lay the foundation for China’s extraordinary economic take-off.

On one of the first occasions I met him in 1999, Cao was in an ebullient mood. I had invited him to dinner with the then editor of the Financial Times and other colleagues who had flown out from London. As we sat down in one of Beijing’s smartest hotels, he made an impromptu order of lobster. It arrived a few minutes later on a bed of ice in a rattan boat graced by a mainsail carved from a white radish. When the bill arrived at the end of the meal, the lobster we had eaten was revealed as one of the Australian airfreighted variety that cost $300 a pop. “No wonder they call him Mr Bankruptcy,” the editor said later.

But during that convivial dinner, during which Cao had charmed us with his wit and insights, he said something that has stuck with me ever since. I came to view it as akin to a basic line of software code that has determined the ebb and flow of China’s fortunes since the CCP came to power in 1949. It has also set the tone for Beijing’s posture in the world.

“If the reforms are too fast, there is chaos. If the reforms are too slow, there is stagnation,” Cao said.

In one sense, this mantra seems self-evident. Without the liberalisation of controls on the economy, growth may slow and eventually stop. But when the pace of liberalisation runs too fast, social and political chaos may follow. This has meant that China’s rulers are constantly navigating between the Scylla and Charybdis of growth and control. To get more of one, they often have to sacrifice a measure of the other. But too much of either holds the threat of perdition.

Cao himself had been a victim of this see-saw polity. His bankruptcy law, which was approved in 1986, was one of a plethora of reforms that put growth into overdrive, contributing to the supercharged inflation and rising tide of official corruption that fuelled huge popular protests in many parts of the country in 1989. When a group of hardline leaders imposed martial law in Beijing in May 1989, Cao led a daring effort to avert the massacre that was to follow.

He and another scholar, Li Shuguang, tried to argue that using the army against the people would be unconstitutional. He also collected signatures calling for the National People’s Congress, the rubber-stamp national legislature, to impeach Li Peng, the leader who had declared martial law.

The effort failed, but not before Cao had managed to collect 57 signatures from members of the congress’s top committee in support of Li’s impeachment. As tanks rolled down Beijing’s Avenue of Eternal Peace towards Tiananmen Square on the evening of June 3, Cao was arrested and thrown in jail, where he remained for just under a year. The leader whom he had advised, Zhao Ziyang, the reformist general secretary of the CCP, was purged from his position after the massacre for opposing the imposition of martial law. He lived under house arrest until his death in 2005.

Although Cao suffered personally for his actions and his career was blighted, his contribution to China’s economic dynamism is undisputed. The embrace of bankruptcy helped school China’s state-dominated economy in the ways of risk and reward. The full spectrum of personal motivation this unleashed has led, over time, to the emergence of a private sector that still drives the lion’s share of economic growth today.

Cao remained iconoclastic until his death. On one of the last occasions we met, he was engrossed by the irony of the Communist party presiding over an economy that owes its prosperity largely to private enterprise. “They should change their name. The China Social party would be a good name,” he said. “Or they could become a football team.”

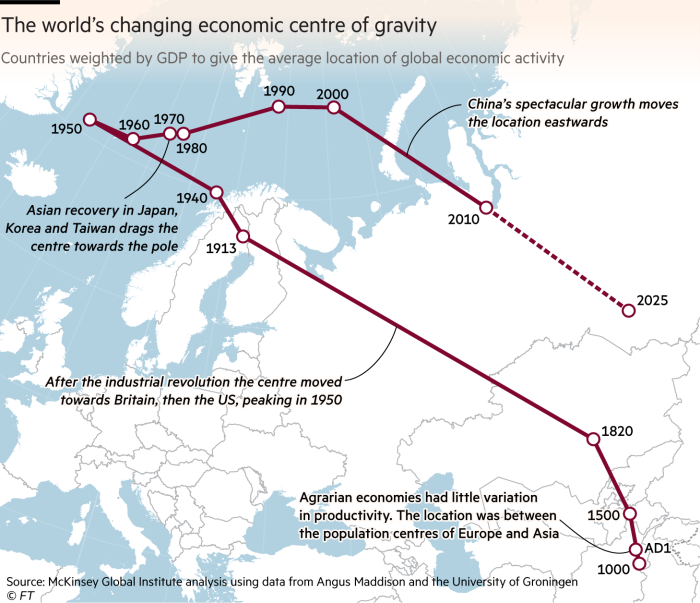

The economic emergence spurred by the reforms has led to the biggest and longest-run economic boom in history. In 1980, China’s annual gross domestic product stood at a mere $191bn, or $195 per capita, making it one of the poorest countries in the world. Nearly 40 years later, its GDP has increased 75 times to $14.3tn, or $10,261 per capita, in 2019. On its current trajectory, it may overtake the US as the world’s largest economy in about a decade or so.

It is well known that such achievements are the products of economic reform. Deng Xiaoping, the diminutive political survivor who became China’s paramount leader in 1978, is rightly credited with a clutch of commercial liberalisations that included the de-collectivisation of agriculture, the opening of China to foreign investment, the lifting of price controls and the rolling back of state ownership, to name just a few.

But what is much less recognised is that a series of political reforms engineered by Deng played an equally crucial role. Deng had harrowing personal reasons for seeking to curb the CCP’s tendency toward capricious and brutal dictatorship. He had been purged from high office at the start of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) by Mao Zedong, the revolutionary leader who founded the People’s Republic in 1949, and spent four years working in a tractor factory operating a lathe.

But this was not the worst of it: his family were attacked by ultra-leftist Red Guards whipped up into a frenzy by Mao’s charges that Deng was a “capitalist”. In one of these attacks, his eldest son, Deng Pufang, was ejected from a fourth-storey window and became a paraplegic.

With this background, it is not surprising that Deng’s political reforms targeted the CCP’s tragic flaw: that concentrated power, if left unchecked, slides ineluctably into political viciousness and economic stagnation. He instituted checks and balances that curbed the power of national leaders and allowed enough freedom to allow a market economy to flourish.

The most crucial of these reforms was the imposition of limits, written into the constitution, which meant China’s president could serve no more than two five-year terms in office. He also advocated rule by a “collective leadership” as opposed to the dictatorship of one man. The constitution was further revised in order to protect the civil rights of individuals. A series of smaller safeguards were also adopted.

“The cornerstone of these reforms was the de facto term limits on the top position in the country . . . with the aim of preventing another dictator like Mao taking over,” says Richard McGregor, author of The Party: The Secret World of China’s Communist Rulers and a former FT journalist.

As a foreign student at a university in central China in 1982, I remember the palpable excitement that Deng’s early reforms brought. One day, a university official lined up the Chinese students into rows on the campus’s dirt running track. He told them to look down at the cotton plimsolls they were wearing. He then proclaimed through a loud hailer that Deng’s reforms would mean that some people in China would have a chance to wear leather shoes.

“University is a single-plank bridge,” he shouted. “It separates those who will always wear cotton plimsolls and those who study hard and then one day may get to wear leather shoes.”

Such material goals were a potent motivation for people who had known the upheavals of life under Mao. My fellow students were born in the aftermath of the Great Leap Forward, which is thought to have killed tens of millions of people. Their childhoods were blighted by the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, which may have led to as many as 20m deaths.

By the time I attended university, Deng had already revised history’s official verdict on Mao. His leadership of the revolution, founding of the PRC and other achievements earned him a rating of “70 per cent right”, Deng ruled. But the Great Leap Forward, the famine it caused, the Cultural Revolution and other “mistakes” made him “30 per cent wrong”.

But on the university campus, it was taking some time for this new official orthodoxy to filter down. The prohibitive cost of reprinting textbooks meant that English language students — many of whom would tell me privately that they dreamt of travelling to the capitalist west — were still learning from texts replete with praise for Mao.

I remember drifting off to sleep in our dormitory listening to students pacing up and down outside reciting lines for the following day’s English lesson. “Chairman Mao is our Great Helmsman . . . the red sun in our hearts . . . ,” they said. “Thoroughly smash the reactionary bourgeois line!”

China under the CCP has been a bonfire for political ambitions. Some downfalls have been sudden and lethal, such as that of Liu Shaoqi, a head of state who was deposed, publicly beaten, hounded as a “criminal traitor” and died shortly afterward in 1969. Other reputations have been gradually deconstructed, airbrushed over time by ever-busy CCP historians. The latter process, though deft, can be no less definitive.

A recent example involved a museum. In the summer of 2018, the National Art Museum of China held an exhibition commemorating the 40th anniversary of the reforms that Deng had done so much to push through.

Visitors were stunned to find a new painting that showed not Deng in the centre of its frame but Xi Zhongxun, the father of China’s current leader, Xi Jinping. The elder Xi, who was a relatively little-known contemporary of Deng’s, is standing and pointing to a map of Shenzhen, where important reforms were initiated. Deng himself is shown seated looking up at the elder Xi with an expression of rapt admiration.

The painting was removed after it caused a furore on the internet. But the incident, and several others like it, have reinforced a sense that Xi Jinping represents a new era in Chinese politics — and one that is proving much more challenging for the west to navigate.

Almost all of the key political reforms instituted by Deng have been thrown out since Xi took power in 2012. He abolished presidential term limits, setting himself up to become the first Chinese leader since Mao to rule until he dies. There is no hint in his court of the “collective leadership” that Deng and his successors advocated and no sign that Xi is grooming anyone to take over.

Instead, he governs as a strongman buoyed by the honeyed praise of underlings and an obsequious media. Provisions in the constitution for freedom of speech, freedom of association and freedom of demonstration carry less weight under Xi than at any time since Deng took power.

Meanwhile, Beijing is outsourcing much of the governance of a country of 1.4bn people to algorithms. Surveillance cameras with facial recognition capabilities on almost every street can keep tabs on where each citizen is and what they are doing. In addition, the digital renminbi — which is being tested in large cities and may be formally launched next year — will allow authorities to monitor in real time every transaction by every person in the country.

Such a pervasive system of digital control is further buttressed by a social credit system that assesses the trustworthiness of individuals, offering discounts on purchases to those with high scores while denying access to services such as air travel to those who slip below certain benchmarks.

Rounding out the picture has been the imposition of a National Security Law in Hong Kong last year, since when scores of democracy activists in the territory have been arrested and jailed. The internment of an estimated 1m Uyghurs and other minority peoples in camps in China’s north-west frontier region of Xinjiang further underlines the freeze in civil liberties.

Thus, a thumping contradiction hangs over China’s future. Beijing presides over a sophisticated, high-tech economy animated by energies that would have been familiar to Milton Friedman. But it does so with a political system that could have been designed by Vladimir Lenin.

The most trenchant critics of this glaring mismatch and of Xi’s tenure have not been foreigners, in spite of Beijing’s regular broadsides against “hostile foreign forces”. They have, in fact, been members of China’s own intellectual elite.

One of these was Cai Xia, a CCP theoretician who had spent her career teaching senior officials at the Central Party School, the most influential repository of party orthodoxy. Last year, Cai was stripped of her CCP membership after audio recordings came to light in which she called Xi a “mafia boss” who ought to be replaced and added that the CCP was a “political zombie”. She went into exile in the US in 2019.

Another leading academic, Xu Zhangrun, has accused Xi of reinstating tyrannical rule. “Tyranny ultimately corrupts the structure of governance as a whole and it is undermining a technocratic system that has taken decades to build,” wrote Xu, who was professor of jurisprudence and constitutional law at the elite Tsinghua University until he was fired last year.

“A party-state system that has no checks or balances . . . invariably gives rise to the rule of a clique of trusted lieutenants. Hence we have seen the equivalent of a court emerge and the political behaviour endemic to a court,” Xu wrote.

For much of the past 100 years of CCP history, power struggles among its elite had little impact on the outside world. But now China is the world’s biggest trading nation, a crucial source of investment and technology as well as home to about a fifth of humanity. Future episodes of the type of disorderly change that has so often sullied the annals of CCP history could plunge the wider world into crisis.

James Kynge is the FT’s global China editor, based in Hong Kong

Data visualisation by Keith Fray, Steven Bernard and Chris Campbell

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first

"control" - Google News

June 25, 2021 at 11:00AM

https://ift.tt/3d9QlU8

Between chaos and control: China's century of revolutions - Financial Times

"control" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3bY2j0m

https://ift.tt/2KQD83I

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Between chaos and control: China's century of revolutions - Financial Times"

Post a Comment