I thought I saw something in the road.

It was after 1 a.m. one night in April 2016, and I was heading home from a friend’s house on the outskirts of Atlanta. From a distance, the dark spot looked like an oil stain. Then she turned her head and my headlights lit her face. A woman in dark clothing was standing in my lane on Interstate 75. I pounded the brake, but I was too late.

Her body crashed into my windshield and her head hit the top of my car before she landed, crumpled, in the middle of the highway. When my car finally stopped, I raced over to her. I felt sure she was dead. But when I reached down to pick her up off the road, she moved.

After the police arrived, an officer took me aside and told me how the investigation would go. The police would impound my car, and if, after 24 hours, it appeared the woman would live, they’d release the vehicle. If she died, or appeared likely to die, investigators would need to test the car’s computer system to make sure the data aligned with my statements.

I spent the next day on the couch, trying not to cry when people called to check on me. Everyone said the same thing: It wasn’t my fault. A police officer on the scene said it. Two men who’d seen the impact from the next lane over said it. The tow-truck driver did too. But I couldn’t stop seeing the woman hitting the windshield, seeing myself slamming down on the brake. Why didn’t I just swerve?

An officer called late that night: I could pick up my car.

“Thank God,” I said. “She’s alive.”

He said he couldn’t legally tell me anything else about her condition, and I wasn’t sure I could handle knowing. I couldn’t stop thinking about her. I imagined that she was paralyzed or had serious brain damage. Flashes of a ruined life flickered in my mind, and I became consumed by a sense of guilt that my friends and family struggled to understand, and that I couldn’t explain.

Only after two years and another crash did I finally resolve to learn what had happened to the woman. One day in 2018, I found her name and an address on the police report. Leaning on a cane, I limped down the driveway and knocked on the door.

As a newspaper reporter, I covered car accidents all the time before my own. For years, my quota was two stories a day, and writing about wrecks was a reliable way to meet it. Metro Atlanta has a lot of them: more than 200,000 a year—one every two and a half minutes.

I wrote most often about vehicular homicides—they were the most serious because they involved a death and an alleged crime, even if that crime was a driver’s momentary failure in judgment. Once, I wrote about a teacher who, according to the authorities, had accidentally turned in front of an oncoming van while entering a parking lot. The van’s driver, a 68-year-old woman, was trapped after the collision. Firefighters found her in critical condition after they cut her out of the mangled van. She was pronounced dead at the hospital. A friend of the teacher contacted me to complain about the story. The teacher was suffering because of what had happened—a death caused by a tiny, common error—and the last thing he’d needed was his mugshot in the paper. I told the friend that I was just doing my job.

After my own wreck, I felt like the stories of people who’d been charged with vehicular homicide could easily have been about me, if the woman I’d hit had died. But there was a key difference: The police said they’d done something wrong. They’d sent a text. They’d failed to “maintain a lane.” They’d switched the radio from talk to music. And someone had died as a result.

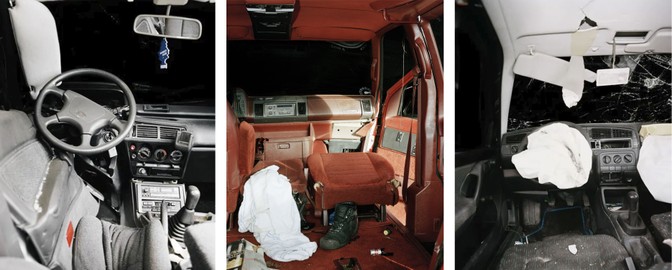

Nearly every time I drove, I thought I saw the woman I’d hit. She’d flash ahead of me, a face in the headlights. Or, if I didn’t see her, I’d imagine her suddenly stepping onto the road. On the dashboard, I noticed cuts in the vinyl from when her back had burst through my windshield. I avoided driving on the highway to work. I took Clairmont Road instead, the slower and, I hoped, safer route. Its four lanes run through leafy neighborhoods, winding past schools, grocery stores, drab strip malls. Still, driving left me feeling under siege, half-crazy about the dangers of this thing I did every day.

Much later, I came across a study in which researchers found that almost 40 percent of people involved in car accidents developed PTSD. Symptoms: frequent, intrusive thoughts or dreams about the accident; fear of driving; feeling isolated even from close loved ones; insomnia—and intense guilt, whether the person was at fault or not.

J. Gayle Beck, a psychology professor at the University of Memphis, is one of a handful of researchers who studies PTSD linked to car wrecks. Being in a serious accident, she told me, “violates our beliefs about how life should be and who we are.” We think we’re in control of what happens on the road. If we’re in control, then we must be responsible.

I stopped covering accidents for a while after mine. When I started again, I imagined myself better at it, more empathetic. One afternoon, I called a man named Ahmad. He told me that two speeding Camaros had passed him on I-285 and collided. He’d pulled over and seen two men who’d been flung into the road; one was dead, the other dying. Inside one of the cars, a young woman was dead.

“I was literally surrounded by death and I was the only one who was okay,” Ahmad said. I could tell he felt guilty, even though he’d had no part in the accident. I asked what he did after the wreck. He said he went home and tried to take a shower. But why, he wondered, couldn’t he touch his body after seeing all that blood?

I wanted to tell him about what had happened to me, that he’d feel better if he just waited. But there in the crowded newsroom, I feared that my co-workers would overhear. Even some of my closest friends didn’t know about my wreck; I was ashamed and still grieving what had happened to the woman, or what I imagined had happened to her.

I just told Ahmad that I was sorry.

I thought I saw a car veering toward me.

It was a bright morning in February 2018. I was driving to work on Clairmont Road when a car suddenly appeared to be merging into my lane from the right, bound to hit me.

This time, I did swerve. I wrenched the wheel and turned into oncoming traffic.

I hit a Ford F-250, an enormous pickup. The crash was 100 gunshots, a bomb detonating. My windshield became shrapnel. My car—a Ford Fusion sedan—crunched, and the dashboard collapsed on top of my legs.

For a moment, after the roaring impact, the silence was a vacuum. I thought I saw the scene from outside my body—from above, from the pine trees: my car, sideways in the road; my arm hanging out of the shattered window. Then I heard myself screaming. “Help me! Help me!”

The driver of the pickup ran over, seemingly unhurt, and asked what he could do.

“Help me get out, please!”

That was impossible. Firefighters had to cut the car apart to pull me out. After the dashboard was lifted from my legs, I passed out from the pain.

I woke up to piercing light, in a fentanyl-induced daze. A breathing tube had been inserted in my throat. My Aunt Josie, my late mother’s twin, stood over me with my girlfriend, Dana. One of our silly couple things was blinking at each other, which she claimed was how cats kissed. I blinked. She blinked back.

The impact had broken my left tibia and fibula, and fractured a bone in my hip. My right femur was in two, my right kneecap shattered. Surgery—to put my left leg back into its socket, repair my right knee, and install a rod to stabilize my femur—took more than 10 hours.

After a month, I went home in a wheelchair. Most nights after work, Dana came over for dinner, and we talked almost exclusively about my legs. We had been dating for a year and had never fought before. Now we fought constantly—mostly about whether I was trying hard enough to recover. When she left at night, we were glad to be apart.

After my short-term disability ran out, I worked from bed. Very slowly, I learned to take steps with a walker, and then graduated to a cane. This was a triumph, but my life felt shredded. Dana and I broke up. I talked with—or at—friends for hours about the lack of public transportation and how American society is set up to force people to drive cars, whether or not they’re good at operating those deadly pieces of equipment. When my friends’ eyes glazed over, I kept going.

I used money my friends donated through GoFundMe to get groceries delivered, and took ride-shares if I needed to travel more than a few miles. But I couldn’t avoid driving forever. I fought panic every time I was in a car. When a pedestrian came too close, my heart raced. At least once, I rolled down the window and begged a man to stay farther from the road.

And I kept thinking about the woman I’d hit. Before my second accident, I’d slowly begun to forgive myself for the first one. Now I kept wondering: Was she in pain, like I was? I decided I had to find out what the wreck had done to her.

“Do you know Anne?” I asked. (I’m using her middle name here to protect her privacy).

I was scared to face her, and was relieved when someone else—a tall, thin man with tattoos up and down his arms—answered the door.

“That’s my sister,” he said.

“I’m the guy who hit her with my car.”

The man didn’t blanch. He seemed almost glad to see me. He said that his family had tried to get details from the police about what had happened but never could, and Anne couldn’t explain.

When I asked how badly she’d been hurt, he said she’d had a small ankle fracture and a cut on her head. The family assumed the wreck must’ve been minor. For a while, they had considered it a miracle.

“What?” I asked.

Anne had struggled for years with mental illness and meth addiction, but in the hospital the morning after I hit her, she told her family that she finally realized she needed treatment, her brother said. The wreck had gotten through to her when nothing else had.

He led me to the living room to talk. He wanted to know what happened that night.

“I saw something dark in the middle of my lane.”

“Right in the middle of the road?”

“In the middle of the road.”

I told him about the impact and the aftermath.

“I picked her up and she started screaming, ‘Get off me! Get off me!’ I pulled her over to one of these concrete-barrier things on the right side of the road. I leaned her straight up and she put her head on it, and I could see blood coming down the concrete.”

Anne had been enraged, telling me to leave her alone as I tried to keep her calm.

Her brother didn’t recommend that I speak with Anne. Her epiphany about getting treatment hadn’t lasted, and she might have decided that the wreck wasn’t her salvation but her undoing, and blame me for it. But nobody else did, her brother assured me.

I felt terrible that Anne was suffering, but relieved that it wasn’t because of me. Driving home, I tried to hold on to that feeling. I tried to keep it from getting away.

After learning to walk without a cane again, I started to wonder about the driver of the truck I’d hit—a man named James. The accident wasn’t his fault, but I thought he might still second-guess himself and feel bad about my injuries. I wanted to do him the favor Anne’s brother had done me.

“I’ll just say right away,” I began on the phone, “I don’t hold anybody at fault for my accident.”

James cut in. “I’m sorry you were hurt, I really am. But we both—me and the gentleman in the car with me—definitely hold you responsible.”

James said he’d regularly cursed my name, especially when my insurance company had refused to pay his medical bills from a brief hospital visit. James had seen the car veering toward me, and thought I should’ve let it hit me instead of swerving into oncoming traffic.

I reminded him that I’d had less than a second to decide what to do.

Yep, he got it, he said. He’d made mistakes too. Just make better decisions in the future. He added that he was mostly mad at the police for not giving me a ticket, because that would’ve made it easier to get my insurance company to pay. I didn’t tell James that I hadn’t deserved a ticket. But I thought it. Emphatically.

I asked James if the wreck had shaken him, like it had me. Nah, he said. Wrecks are part of life. We have to drive. If you survive, you get up and keep going.

After we hung up, I slumped back in my chair. Can I just say, I was pissed at James. At first for blaming me, then for being able to move on when I couldn’t.

I’d asked James if his passenger, a friend named Ricardo, would be willing to talk with me too. A few days later, he called. A retired respiratory therapist, Ricardo had to pay $3,000 in medical bills from his hospital visit after the accident. Like me, he was traumatized. He remembered how normal everything had been moments before our collision, and so whenever he was driving and all seemed well, he’d worry. Peace scared him. He’d bought a big truck to feel safer.

Ricardo said he had occasionally sympathized with me, but mostly he’d hated me. He remembered calling my insurance company to beg for help with his medical bills. He asked the agent if I was alive. She assured him that I was, and Ricardo replied, “Is he in pain? I just want to make sure he’s in pain, because he’s put pain in my life.”

I had to laugh. Despite the harshness of his words, his voice was kind. He said he wasn’t angry at me anymore. He’d recognized that I’d faced a terrible choice, with no time to think it through. He said he was sorry I had been so badly injured; I told him I was sorry for what he had gone through too.

My left leg, stabilized by a titanium rod, is still broken. A metal rod is a decent substitute for a bone, until the rod inevitably breaks too. I’ve had several surgeries intended to encourage the tibia to heal, and none has worked. My surgeon says he’s seen people with similar breaks take up to four years to recover. I hurt every day, but I’ve gotten used to it. I’ve accepted that a person gets one body; it changes.

After five years, I still think that I see Anne on the road. And I still wonder if she was traumatized by the wreck. Is she haunted by what happened to her, like I am?

Anne’s brother suggested I contact their dad, because he was the relative who spoke most with Anne. I texted him to ask if he thought she would be up for talking with me. He said she was still too unwell.

Then he stunned me. He apologized on behalf of his daughter for what she did to me.

“Please forgive yourself,” he said.

I wasn’t to blame, and neither was Anne. On the road, neither of us was in control. Her dad sent a picture of Anne from a recent holiday. In it, she sits next to her teenage son, a beaming boy with his beaming mom. Her hair’s fixed nicely, and she wears a white blouse and a cross on a thin gold chain.

I started to cry, unsure why until I realized this: She looked normal, fine. As if none of this had ever happened.

"control" - Google News

May 03, 2021 at 07:00PM

https://ift.tt/3xLwJOz

We Think We're in Control on the Road. We're Not. - The Atlantic

"control" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3bY2j0m

https://ift.tt/2KQD83I

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "We Think We're in Control on the Road. We're Not. - The Atlantic"

Post a Comment